The weighted average is a powerful tool for investors. It can be used to:

- Evaluate the performance of a portfolio

- Aid in understanding how the broader market moves

- Determine whether a company's earnings power will live up to your expectations.

To understand how the weighted average can achieve all these things, let's start with the nuts and bolts of the calculation.

Weighted averages are used often in investing, especially in how we measure the performance of our respective portfolios. For example, the S&P/ASX 200 Index (ASX: XJO) is the weighted average performance of the 200 largest companies on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) by market capitalisation.

It makes sense that massive companies, such as BHP Group Ltd (ASX: BHP) and CSL Limited (ASX: CSL), will have greater influence on the movement of the entire index than smaller companies at the bottom of the list.

If only a few of the largest companies in the index have a lousy day, while a bunch of the smaller companies do well, the index will typically reflect the woes of those big fish rather than the wows of the little ones.

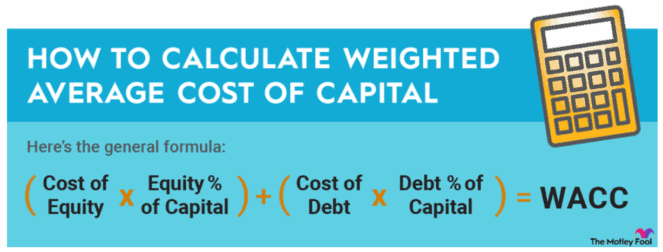

How to calculate the weighted average cost of capital

Here's the general formula for calculating the weighted average cost of capital (WACC):

Here are five steps that will make this easier:

- On a company's balance sheet or annual report, find the total amount of debt and average interest rate on the debt. If a company doesn't specify its average interest, you can find it by dividing its annual interest expense (on its income statement) by its total debt.

- Look at the current share price for the company and write down its market capitalisation.

- Calculate the cost of equity using one of the methods in the next section.

- Add the debt and equity portions of the capital. Divide the equity by the total to determine the equity percentage of capital. Then divide the debt by the total to determine the debt percentage of the capital.

- Plug these values into the formula and calculate the WACC.

Start the calculation with cost of equity

A stock's WAAC starts with an individual stock's cost of equity, which can be derived with either of two methods.

As a long-term investor, you expect the business you have bought into to generate a return. To achieve this, a company's return on invested capital (ROIC) should exceed its cost of capital. Basically, the money it can generate from an investment should be greater than the interest costs on that investment.

There are two main ways companies get capital — by issuing new stock or by taking on debt. The cost of debt is simply the interest expense as a percentage of the total debt. On the other hand, the cost of equity can be evaluated in two different ways:

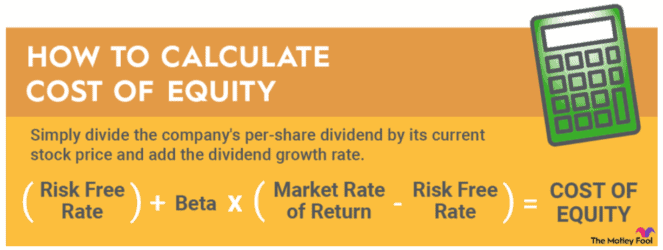

Cost of equity

If a company pays dividends, you can determine the cost of equity by the dividend capitalisation model. This is the easier method of the two. Simply divide the company's per-share dividend by its current stock price and add the dividend growth rate. Here's the formula to calculate the cost of equity using this method:

For example, if each share of Company X trades for $50 and produces a $1 annual dividend, it has a dividend yield of 2%. And, if Company X has consistently grown its dividend in recent years by around 5%, we can add those together to find Company X's cost of equity is 7%.

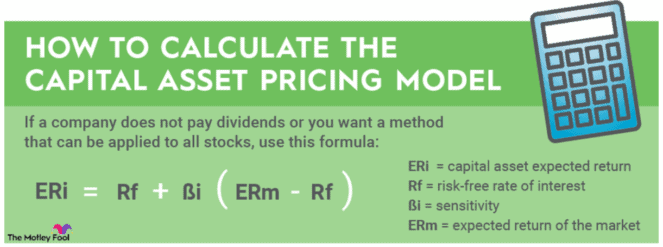

Capital asset pricing model

On the other hand, if a company does not pay dividends or if you simply want a method that can be applied to all stocks, the capital asset pricing model (CAPM) could be the better way to go. This is considerably more complicated and can be calculated by this formula:

Where,

- The risk-free rate of return is typically the market rate for risk-free investments such as Treasury bills.

- The market rate of return is the assumed rate of return for the entire stock market (which can generally be assumed to be 10%).

- Beta is a company-specific metric that refers to the volatility and direction of a stock's typical movements relative to the market. A beta of greater than one indicates a high-volatility stock, while a beta of less than one indicates the opposite. A negative beta implies that a stock generally moves in the opposite direction of the overall market.

Example of calculating weighted average cost of capital

Consider this hypothetical example. Company XYZ has a $100 billion equity market capitalisation and $25 billion in debt at a weighted average interest rate of 4%. The company pays a 3% dividend yield and has increased its dividend at an average rate of 5% per year.

First, the company's cost of equity would be 8% based on the dividend capitalisation model. And, with $125 billion in total capitalisation, equity would be 80% of the capital structure. Debt would be the other 20%. So, we can calculate WACC as follows:

WACC = (0.08x 0.8) + (0.04 x 0.2) = 0.072 or 7.2%

Similar concepts to know

A couple of variations of the weighted average cost of capital are worth mentioning as well:

Marginal cost of capital: The weighted average cost of the newest capital raised by a company or proposed to be raised by a company. For example, if a company wants to sell $100 million in bonds at 5% and simultaneously issue 10 million new shares of stock, the marginal cost of capital would only consider those new additions, not the rest of the company's debt and equity capital.

After-tax weighted average cost of capital: The same calculation method as detailed earlier but with the cost of debt modified to reflect the company's tax rate (since interest can be deducted). For example, a 5% cost of debt and a 20% tax rate would effectively reduce the cost of debt to 4% (5% times 0.2 reduces the cost of debt by 1%).

The Foolish bottom line

While most investors won't regularly perform WACC calculations, this is still an important concept to know. Companies that can raise money at low costs of capital relative to their ROIC may have an advantage over companies that cannot.

Weighted average cost of capital gives investors valuable information about a company's efficiency when it comes to raising capital to put to work for investors. Like any investment metric, it doesn't tell the whole story by itself, so investors should use it as part of a more thorough investment analysis.