Have you ever wondered how global companies maximise value by returning profits to their shareholders? While some companies choose dividends, — appealing to investors with their direct cash returns and tax implications — others often opt for stock buybacks to potentially increase share value and earnings per share. What influences these decisions? How do tax policies and market conditions sway corporate strategies? In this article, we delve into the financial tactics of dividends and buybacks, understand their impacts on investor returns, and see real-world examples of each strategy in action.

Premium content from The Stars and Stripes Team

There are many reasons to diversify your investment portfolio internationally. Some of these include the high industry concentration in the Australian share market (particularly the large proportion of banking and resources), access to unique market segments (such as technology in the United States and luxury goods in Europe), and to reduce the risk of having all of your investments in one nation (where politics, tax rates and the economy can change). Yet there are important nuances to consider when venturing outside of Australia, as the investing environment can differ from country to country. One important factor is the tax environment and its influence on how a company chooses to allocate its funds – in particular, the payment of dividends.

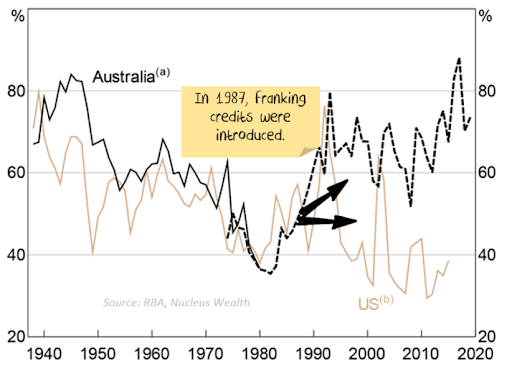

Dividends are extremely popular in Australia. In general, ASX-listed companies start paying dividends much earlier than their international counterparts, and pay out a higher proportion of their annual profits to shareholders. This is largely due to the dividend imputation system, which is most commonly known as 'franking.'

The imputation was introduced in 1987 and entitles shareholders to a tax credit alongside their dividend for the tax already paid on these profits by the company. In Australia, company profits are usually taxed at 30% (or 25% for small businesses), meaning that investors who receive a "fully franked" dividend are generally required to only pay tax on the difference between 30% and their marginal tax rate on the dividends they receive. This is designed to avoid the government taxing the same profit twice (once on the company and then again on the individual). While there is also a dividend imputation system in New Zealand and a few other markets, they are generally quite rare.

Dividend Payout Ratios in the Australian and U.S. Share Markets

Source: Nucleus Wealth

Double taxation of dividends is one of the main reasons why the payout ratio (that is, the proportion of profits paid out in dividends) is generally lower in the U.S. However, this doesn't mean that U.S. companies are less willing to return company profits to shareholders. Instead, many profitable U.S. companies choose to do this via share repurchases, or what are commonly known as buybacks. While the concept might seem a little abstract, essentially the company uses its profits to buy shares of the company back from shareholders. This reduces the number of shares that the company has on issue/outstanding and increases the ownership of the remaining shareholders. Put simply, there are less slices of the pizza and each remaining slice gets a bigger share of the company's profits.

Buybacks: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

Share buybacks have received a lot of negative media coverage in recent years, particularly in the U.S. where a tax on buybacks was introduced as part of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (the 1% excise tax applies to companies that repurchase more than US$1 million of stock over the course of a tax year). Part of this negativity undoubtedly surrounds the ability to avoid the tax on dividends, as well as a perception that buybacks reduce a company's willingness or ability to invest in their businesses and employees, and are designed to benefit senior management teams that have their compensation tied to figures that can be boosted by share buybacks. Like everything, however, buybacks can be either valuable or detrimental to the remaining shareholders, depending on the price at which they are executed. We can look no further for a clear explanation than Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE: BRK.B) 2022 Letter to Shareholders:

The math isn't complicated: When the share count goes down, your interest in our many businesses goes up. Every small bit helps if repurchases are made at value-accretive prices. Just as surely, when a company overpays for repurchases, the continuing shareholders lose. At such times, gains flow only to the selling shareholders and to the friendly, but expensive, investment banker who recommended the foolish purchases.

Gains from value-accretive repurchases, it should be emphasized, benefit all owners – in every respect. Imagine, if you will, three fully-informed shareholders of a local auto dealership, one of whom manages the business. Imagine, further, that one of the passive owners wishes to sell his interest back to the company at a price attractive to the two continuing shareholders. When completed, has this transaction harmed anyone? Is the manager somehow favored over the continuing passive owners? Has the public been hurt?

When you are told that all repurchases are harmful to shareholders or to the country, or particularly beneficial to CEOs, you are listening to either an economic illiterate or a silver-tongued demagogue (characters that are not mutually exclusive).

What We Look For

The late Charlie Munger, Warren Buffett's longtime business partner, listed "look at the cannibals" as one of his three top ideas for finding outperforming investments. Cannibals are typically defined as members of species that eat their own kind, and Munger used this metaphor to describe companies that "eat" their own shares. A great example of this would be NVR (NYSE: NVR), which has reduced its number of diluted shares outstanding by 30% over the past 10 years and a whopping 60% over the past 20 years – all while significantly growing its market share, revenue and profits.

As described in the Berkshire Hathaway Letter to Shareholders above, it's important to consider not just the total amount spent by the company on buybacks, but also the share prices at which management is able to execute the repurchases. Here a great example is W.R. Berkley (NYSE: WRB), where founder and Chairman Bill Berkley has proven extremely adept at timing share repurchase activity, buying back approximately US$1.7 billion in WRB shares over the past 10 years at an average price of around US$32 – that's a considerable discount relative to the approximate US$85 share price today!

Dividends: The Good, The Bad and the Ugly

There are many advantages to a company paying dividends. According to investing theory, three of the main reasons are "signalling," "bird in the hand" and "agency" theory. Signalling refers to the fact that company insiders have more information about the company than outside shareholders and can convey information about how well the company is doing through the size and consistency of the dividend. Bird in the hand is quite intuitive and says that all else being equal, investors would prefer to receive cash today given the uncertainty of greater dividends or capital gains in the future.

Agency theory is about the separation between the owners of the company (the shareholders) and the management team. The big concern here is management wasting the cash, often on big acquisitions that are either a gross miscalculation or are designed to build the manager's empire. This can be a big risk in highly cyclical industries such as oil and gas, where companies can become flush with cash at the top of the cycle and believe the good times will last forever.

Other reasons for a high payout ratio can be that certain shareholders rely on the income stream (such as retirees), shareholders with beneficial tax rates (some may even receive refunds from the franking credits) or those that are banned from spending the shares' principal balance (such as trust and endowments).

On the other hand, the most obvious negative of a dividend is the tax expense – particularly when compared to capital gains, where the tax impact is deferred until the investor sells the investment. This might not seem like a big deal on any particular investment, but over time the strategy of deferring taxes can have a very big impact on your ultimate wealth.

Additionally, one advantage of buybacks over dividends is that its timing is completely up to the company's management. This can allow the company to pause buybacks to maintain a healthy cash buffer during more challenging times, or to accelerate growth in its core business or through a merger if opportunities arise. Cutting or fully removing a dividend can have a dramatic impact on a company's share price, which can far outweigh the amount of the dividend itself. What's more, timing of buybacks can be extremely beneficial to an investor's long-term returns, if they are attractive prices (see the Berkshire Hathaway 2022 Letter to Shareholders).

Foolish Takeaway

There are many factors that influence whether a company pays a dividend, repurchases shares, or does both. Some of the most important variables are the company's industry (is it cyclical?), the business model (is it transparent or opaque?), how big the company's growth opportunities are (is it mature or early stage?) and how strong and regular the cash flows are. One thing to keep in mind though is that while it is certainly appealing to receive cash back from your investment in the form of dividends, there is a cost to this (higher tax) and it does reduce the company's ability to invest in its growth opportunities. Buybacks defer this tax impact and provide management with a more flexible way of returning capital to shareholders, as well as the opportunity to add even greater value if they are executed at attractive prices. One simple method we have for evaluating this is if we are interested in buying shares at the current price, wouldn't we want the company to do so as well?

The two are not mutually exclusive, however, and W.R. Berkley provides a great example of how management can use a combination of ordinary dividends, special dividends and share repurchases to enhance shareholder returns. The most important thing is that management has the shareholders best interests at heart and is looking to return excess capital to them in an optimised and tax-efficient way, while not depriving the company of attractive growth opportunities by paying out too much of the company's profits.