Investing can be a tricky game – just the act of choosing one single company (or fund) at a time out of thousands of options to deploy your hard-earned cash into requires a lot of intestinal fortitude and conviction. For example, if you've chosen a stock based on what you perceive as a cheap price, you are doing so because an army of other investors are avoiding your choice like the plague.

You have to weigh up the risks and regards, the positives and negatives of every choice, because (unfortunately) your capital is limited whereas your choice of investments is almost unlimited.

Every investment is a choice but also has a cost. Sure, there are your normal costs associated with investing, such as brokerage, fees and taxes.

But I'm talking about opportunity cost here.

Like most things in finance and economics, every cost can be measured not just with money, but with what you're not buying.

When you're going out to pick up a new car, buying a Ford will normally mean you're not going home with a Toyota.

Similarly, if you really like two ASX companies – say Commonwealth Bank of Australia (ASX: CBA) and BHP Group Ltd (ASX: BHP) – but only have $500 to invest, you're going to have to choose. The cost of picking up some CBA shares is not only $500, but also the opportunity to own BHP.

Of course, you could just buy an index fund like Vanguard Australian Shares Index ETF (ASX: VAS), which buys you a small piece of every ASX company out there, but even doing this might exclude you from owning the iShares Global 100 ETF (ASX: IOO) or the US-focused iShares S&P 500 ETF (ASX: IVV).

Every investment has a cost and shuts you off from another one.

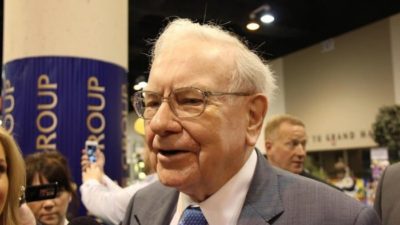

So every time you think about buying some shares, making sure there's not another better option out there sounds elementary (dear Watson), but is foundational for investing success. As Warren Buffett says, you don't have to swing at every pitch that's thrown at you, you just have to wait for the perfect ball.