This article was originally published on Fool.com. All figures quoted in US dollars unless otherwise stated.

The world's biggest brick-and-mortar retailer just escalated its price war with the world's biggest e-commerce retailer. That is, Walmart (NYSE: WMT) is subsidizing price cuts it requested of some third-party sellers offering their goods at Walmart.com. The move, according to Bloomberg, appears to be a response to a similar price-lowering strategy Amazon.com (NASDAQ: AMZN) put in place in August.

It's clearly good news for shoppers, and it's not bad news for the merchants utilizing Walmart's e-commerce venue. It may even be good news for those vendors, as lower prices for consumers may improve their total sales volume. The losers in this paradigm are investors, who are supplying the subsidies in the form of thinner profit margins.

Even so, if Walmart handles the new strategy effectively, it might be well worth the added cost of doing business.

Walmart responds to Amazon's pricing pressure

Walmart hasn't detailed just how many vendors or items will be part of the so-called Competitive Price Adjustment program, and though it's meant to be a temporary initiative, some speculation has surfaced that Walmart could maintain the program as long as Amazon keeps its similar program in place.

The $64,000 question is, of course, "Where will the money to offset vendors' price cuts come from?"

Answer: Most likely, it will be added to the "cost of goods sold" line on the income statement, though it's conceivable the retailer could somehow work it in as a selling, general, and administrative expense. How much the program will cost the company is completely unknown, but against Amazon, it could be sizable enough to notice.

Either way, the subsidy will shave the company's total net income at a time when gross profit and net profit margins have been pressured by the growth of its e-commerce division and higher wages for its employees.

Another dent in overall profitability

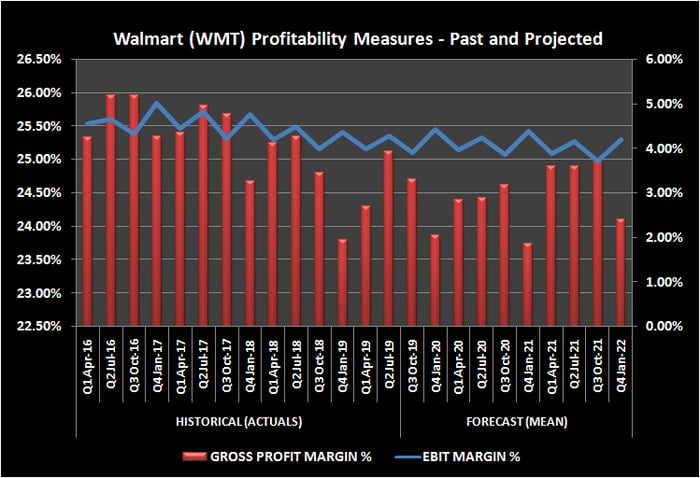

The absolute change in Walmart's recent profitability measures is seemingly modest at first glance. In the highly competitive world of retail, where margins are usually paper-thin, though, every penny counts.

The chart below puts things in perspective. Last quarter's gross profit margins on goods sold rolled in at 25.1%, down from 25.35% a year earlier. A year from now, analysts anticipate Q2 gross margins of 24.4%.

Data source: Thomson Reuters.

Earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) margins are clearly no better, trending lower since 2017 when Walmart turned up the heat on its e-commerce efforts and began funding higher hourly wages for store employees. The second quarter's EBIT came in at 4.28% versus 4.49% in Q2 of the prior year. Next year's second-quarter EBIT profit margins are projected at 4.24%. The deterioration of both measures is clearly part of a much bigger downtrend.

That's not to suggest better pay for hourly workers was ill-advised. Ditto for an expanded e-commerce initiative, which forces retail prices lower without lowering Walmart's wholesale costs. Although third-party vendors provide many of the goods sold via Walmart.com, much of the online inventory is Walmart's own, and it is often sold out of stores at a price lower than the store's tagged price. The company offsets thinner margins with more volume.

Still, investors reasonably expect the retailer to handle the trade-off attentively and thoughtfully. That's where questions remain.

Making lemonade

Walmart deserves credit for penetrating an e-commerce market that's clearly controlled by Amazon.com. Thinner margins were always going to be part of that paradigm. In the end, price competitiveness is the crux of the battle.

If Walmart is going to escalate the conflict on the price front of the retailing war, however, it may want to borrow a page from the Amazon playbook and start collecting and monetizing data about its customers.

What that might look like isn't entirely clear. Amazon uses customer information to sell several kinds of services in addition to physical goods, including Prime. Its planned grocery stores aren't just about groceries. It's another way of establishing a relationship with consumers and eventually selling them one or more of Amazon's private-label goods -- or, more recently, selling ad space. Walmart doesn't quite have a mechanism to apply the same kind of leverage. If the retailer expects investors to digest shrinking margins stemming from an extended price war, however, it may have to build one.

This article was originally published on Fool.com. All figures quoted in US dollars unless otherwise stated.