Instead of researching and picking individual stocks, institutional and individual investors may instead outsource the exertion of stock picking to others willing to do it full-time and (presumably) with more acumen.

But, more and more, this acumen and its price are coming into question.

Active management actively underperforming

In Australia, a 2015 report by Vanguard Research found "62% of Australian large-cap equity funds underperformed their benchmarks over the ten years ended December 31, 2014."

Further, when adjusted for survivorship bias (properly accounting for the performance of liquidated funds prior to closure), the proportion of underperforming funds went up from 62% to 77%.

In the UK, Neil Woodford – one of the most prominent fund managers in the world – locked investors out of his main fund after a stretch of poor returns. This led two Bloomberg Intelligence analysts to write that the "redemptions freeze by Neil Woodford's fund could further damage the reputation of active management, serving as another catalyst for the move toward passive investing."

Bloomberg also reported that, in the US, about 4 in every 10 dollars are invested in schemes mimicking an index. According to Forbes, since 2006, investors withdrew $1.2 trillion from actively managed US equity mutual funds, pouring $1.4 trillion into equity ETFs and index funds.

Not only that, Moody's reported that outflows from active funds have accelerated. In 2018, active funds saw the "highest annual recorded outflows since data has been gathered."

Most strikingly, Moody's Investors Service predicts that "adoption of passive investing is on track to overtake active investing" as early as 2021.

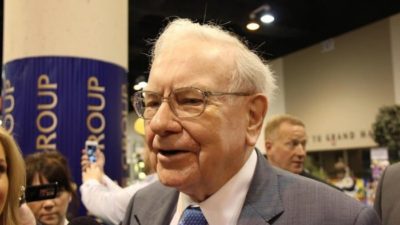

The downsides of active funds famously led Warren Buffett to enter a bet with hedge-fund manager Ted Seides in 2007. Buffett wagered that a plain S&P 500 index fund would outperform a basket of hedge funds over a decade.

It is a dangerous game to bet against oracles and so it proved for Seides. Buffett's chosen index fund recorded annualised returns of 7.1% while Seides' basket of hedge funds had annualised returns of 2.2%.

Buffett explained his reasoning in a letter to shareholders, writing:

A number of smart people are involved in running hedge funds. But to a great extent their efforts are self-neutralizing, and their IQ will not overcome the costs they impose on investors. Investors, on average and over time, will do better with a low-cost index fund than with a group of funds of funds … Performance comes, performance goes. Fees never falter.

While the shift away from active management may seem recent, pointing out the negatives of active funds is not.

For instance, Burton Malkiel, in his 2003 edition of A Random Walk Down Wall Street, wrote that, "for the 20 years ending December 31, 2001, the average actively managed large cap mutual fund underperformed the S&P 500 large cap index by almost 2% per year."

Successful actively managed funds

Of course, there are successful actively managed funds – after all, without visible winners there would be no sustained willingness to participate in actively managed funds.

The Australian government's sovereign wealth fund – Future Fund – made a sizeable 11.5% return over the 2019 financial year. As the AFR Weekend reported, a "strong contribution" to these gains came from the Future Fund's allocation to numerous hedge funds.

Two of the chosen hedge funds were Ray Dalio's Bridgewater and the esoteric quant fund Two Sigma. Last year, Bridgewater's Pure Alpha returned 14.6% and Two Sigma's Absolute Return gained 11%.

It is important to note, however, that while these funds recorded strong returns, it was not a good year for hedge funds in general.

As the Financial Times reported, last year was "among the worst for hedge funds since the financial crisis … with the average hedge fund losing 6.7%."

For comparison, according to Stockspot's 2018 Australian ETF Report, Australian shares (broad market) ETFs had an average return of 2.1% after fees with 4% dividend yield. Global shares (broad market) ETFs had a high average return of 12.8%.

Additionally, even Future Fund prefers less exposure to active management. As the AFR Weekend reported, "to gain exposure to equities, the Future Fund does not hire active 'long' only managers, preferring to gain exposure through specially designed indices that aim to track particular factors."

Past successes don't always beget future successes

One may argue that given a large enough distribution of an enterprise like active management, mediocrity is a mathematical certainty. What matters is picking winners and serial winners do exist.

So, say an investor found a historically successful active fund: can the investor predict the fund will persist to perform well in the future?

As reported by the 2015 Vanguard Research report, a 22-year long study by Nobel Prize-winning economist Eugene Fama found "that it is extremely difficult for an actively managed investment fund to regularly outperform its benchmark."

Worryingly, the report found that an "investor selecting a fund from the top 20% of all funds in 2009 stood a 27% chance of falling into the bottom 20% of all funds or seeing his or her fund disappear along the way" in the subsequent five-year period.

Foolish takeaway

Ever since the founding of the pioneering index fund Vanguard, rumblings about the underperformance and costliness of active funds have grown. These days, the rumblings are loud and clear.

Investors are walking the disgruntled talk and transferring their money from active to passive management. And as long as ETFs and index funds continue to provide very low-cost, robust returns, the march away from active management will continue in tandem.